Health insurance companies are aggressively expanding to adjacent markets and services, a strategy that has led insurers to make venture investments in companies that provide or enable health care services. In 2017, for example, UnitedHealth Group created Optum Ventures with an initial $250 million investment; the fund currently has more than $1 billion under management. Similar funds have been created at virtually every major insurer.

Given their extraordinary leverage – their ability to set payment rates, establish proprietary networks, and contract for services – there is reason to be concerned that insurers are using venture investing to “self-deal” to boost profits rather than drive innovation in care delivery.

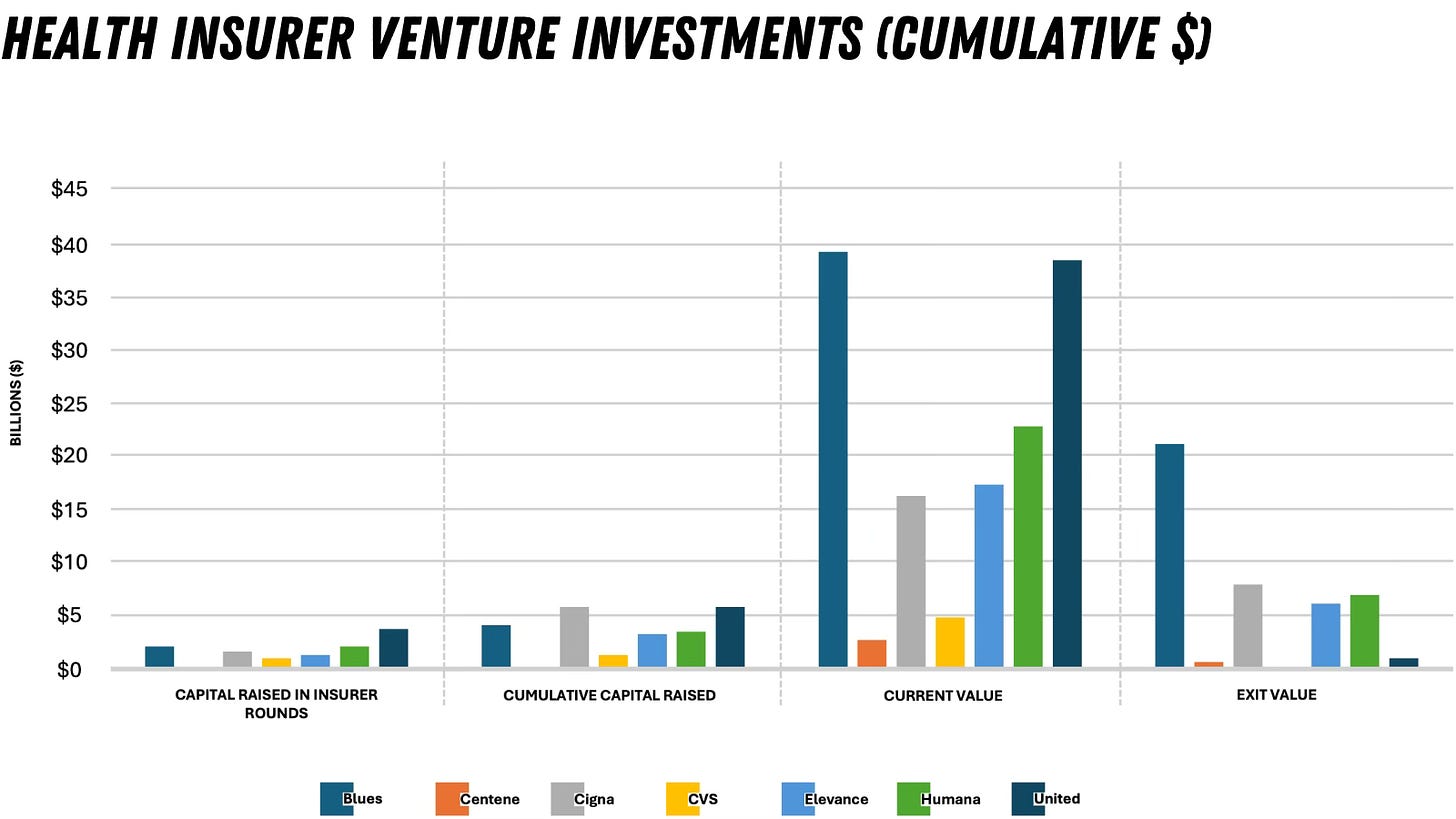

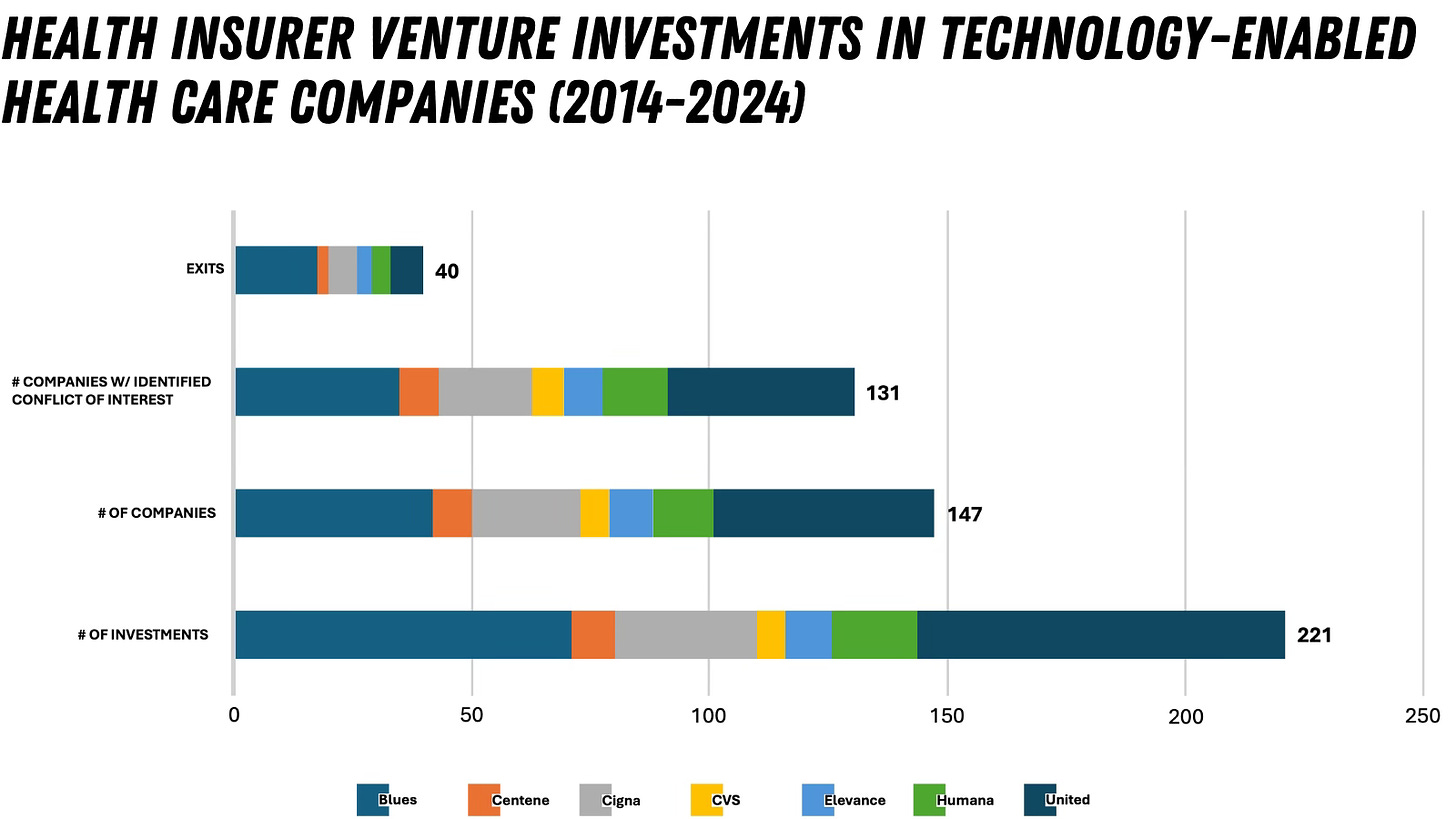

Over the past decade, health insurers have made 221 investments in 147 companies that either deliver or enable clinical services: United (77 investments in 46 companies); Blue Cross Blue Shield (71/42); and Cigna (30/23) are the most active. The most common company types were technology-enabled services, including specialty care (23%) and behavioral health (18%).

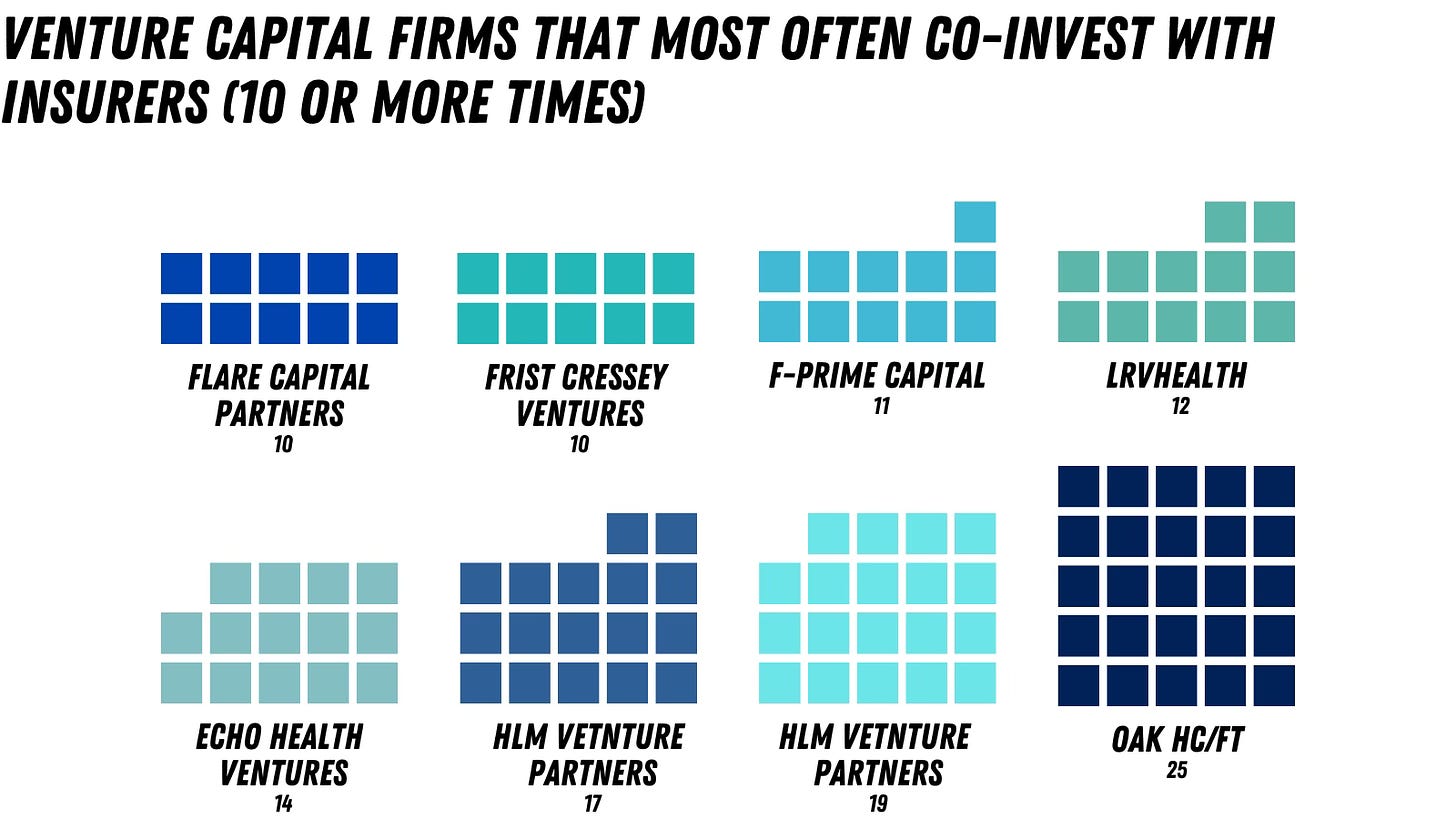

There were a handful of venture capital firms that commonly partnered with insurers on these investments.

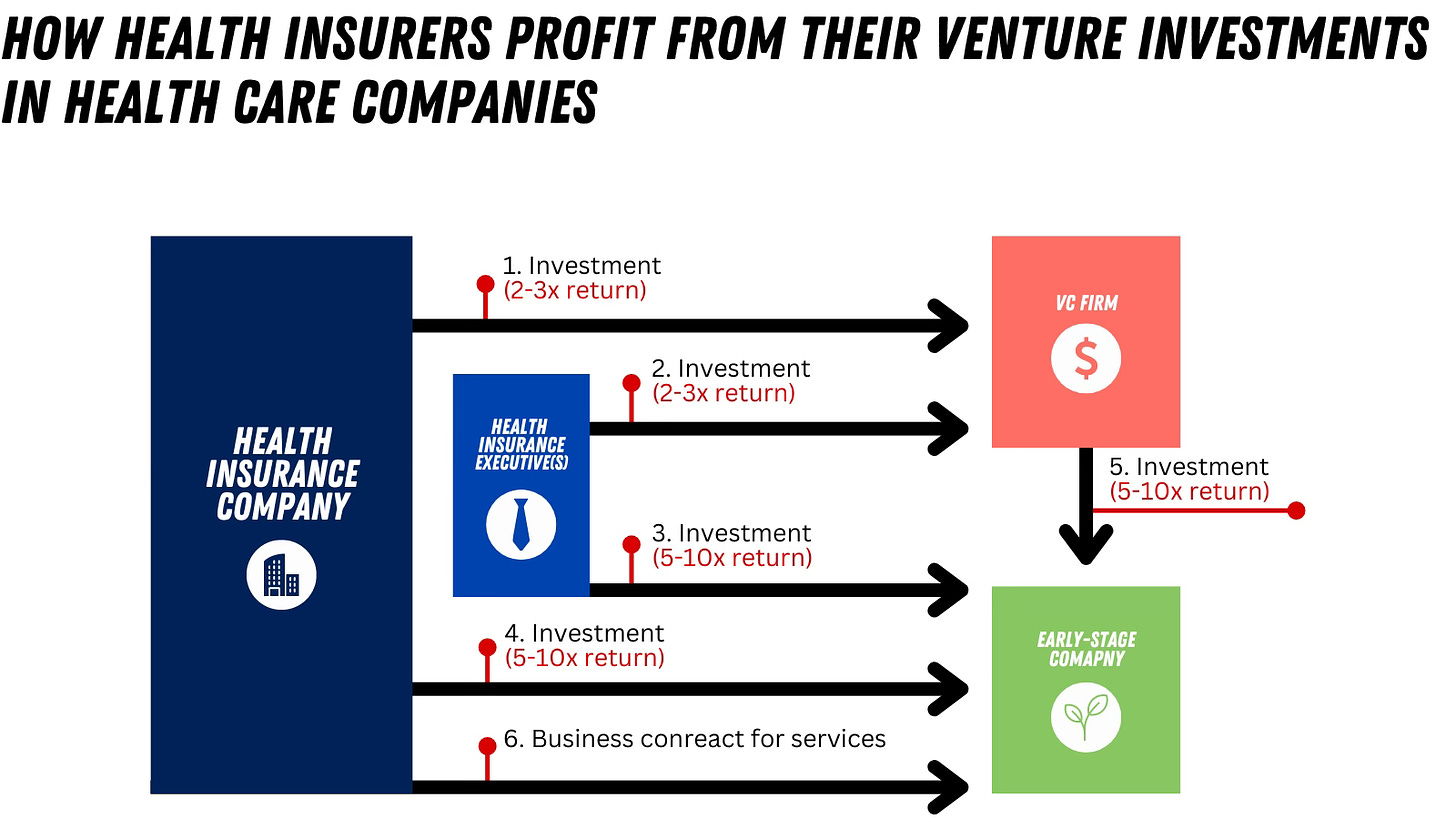

Health insurers and their executives can profit in multiple ways in these deals. The insurer can invest in the VC firm that is the primary backer of the company and can also invest directly in the company. Insurance executives can also invest directly in the same VC firm and invest directly in the company as an angel investor. Unlike ordinary investors or even sophisticated investment funds, insurers have a unique way to ensure their investments pay off – by entering into a direct business arrangement with the same company. This usually takes the form of a contract for services but can also include preferential placement in provider networks, favorable payment rates for clinical services, or crafting medical policies with coverage determinations that benefit the company. In fact, we found evidence of this type of activity in 89% of the portfolio companies, indicating widespread potential conflicts of interest.

This parallel activity impacts the valuation of early-stage companies to the benefit of insurers. These companies are commonly valued at a revenue multiple, so a contract with an insurance company can catapult their valuation from near zero to $50 million-plus overnight. The carefully sequenced activity of contracting and investing in the same company maximizes returns and minimizes risk for insurers in a way that is impossible for nearly any other investor to do.

This investing scheme is yielding remarkable results for insurers. The total capital raised by the portfolio companies was $24.2 billion with the majority raised during rounds in which the insurers led or participated; these companies currently have an estimated cumulative market value of $142 billion. There have been 40 exits (acquisitions/mergers), including five initial public offerings (IPOs). The current cumulative market value of the five IPO companies is $6.8 billion versus $11.2 billion at the time of their IPOs – a 40% decrease during a time (2019-2024) when the S&P had a positive return of 131%. This indicates that while insurance companies profited handsomely from the IPOs, the value of the underlying services did not hold up to the scrutiny of the public markets.

This is the tip of the iceberg since the overwhelming number of companies are still private and camouflaged from the public and regulators’ view. We lack transparency about which insurers are limited partners in the VC firms in which they co-invest, the timing and nature of business relationships with their portfolio companies, precise funding amounts and returns, and the identities of participants.

While there are unarguable benefits from investments in innovative health technologies and services, they can have the opposite effect and adversely impact patient outcomes and costs. The enormous capital insurers devote to venture investing diverts resources from efforts to improve quality and costs for patients and clinicians. For example, health insurers could choose to increase payment rates to contracted behavioral health clinicians (who notoriously opt out of insurer networks due to abysmal reimbursement) instead of investing enormous capital on start-up mental health companies. And since a significant number of early-stage companies focus on vulnerable populations, including the poor, elderly and people with serious mental illness, another concern is the degree to which companies undergo thorough evaluation to ensure their clinical efficacy and safety.

Action is needed to ensure integrity in venture investing by powerful insurers. Here are several common-sense recommendations:

Insurers that receive substantial revenue from federal programs such as Medicare or Medicaid should be required to disclose conflicts of interest in related investment activity, including the nature of business relationships with portfolio companies and individuals (insurer board members and executives) with potential conflicts as direct investors in the companies or VC firms.

Insurers and VCs should establish and publish clear methods for managing potential conflicts in joint investments.

Insurers should disclose potential conflicts to providers in their network, who may refer patients to services promoted by the insurer, and to their health plan enrollees, who may use the services offered via a VC-backed company.

More robust data reporting and research using advanced analytics and artificial intelligence is needed to identify patterns of potentially illegal activity in venture investing.

At minimum, we need greater transparency and accountability to ensure that venture investments in our health care system drive meaningful changes, beyond just enriching powerful insurance companies and their co-investors.

I should mention that I ran my findings by two prominent venture capital investors. The first acknowledged this as a problem and encouraged me to keep going. The second became very defensive and gave a full-throated defense of the status quo, even claiming that insurers do not profit from venture investing. Both responses give me conviction we need accountability and action on this issue.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2efc1ef1-ba0b-4ca3-b9f6-a9a790da4b38_1344x256.png)