Expert Q&A: Value-Based Kidney Care

How 6 industry experts think about progress, pitfalls, and potential in this space

Welcome to our third Signals Expert Q&A, the series that that asks industry leaders to weigh-in on pitfalls, progress, and potential in their respective areas of expertise in the Kidneyverse.

This month, we're diving deeper into one of the most funded yet least understood sectors of healthcare: value-based kidney care. If you’re a regular Signals reader, you’ve followed our coverage of this space in recent months, including our (a) table of top value-based care players, (b) preview of a potential VBC bubble after 2023 megadeals, and an (c) update on participating KCC entities. It’s time to fill in a few finer details that only on-the-ground expertise can provide. Today is about balancing optimism with checkbooks; and expectations with reality.

Today, we’ll learn how 6 experts think about value-based kidney care. Over the course of 7 questions you’ll get to know how they see the challenges and opportunities ahead of us, the role of policy in shaping the value-based landscape, important lessons learned along the way, and what the world looks like if we get it right.

Whether you are an industry veteran or just starting out, this Signals Q&A will give you an inside look at how value-based kidney care works, what’s holding it back, and a few ways we might make it better… for posterity.

Reading time: 40 minutes.

Meet our experts

Our experts represent a broad range of insights and experiences, including academia, advocacy, and industry. Today, they shape our understanding of the impacts of these care models on society, raise awareness and support at the federal level, and provide care for hundreds of thousands of lives across the country. I’m grateful for their leadership and for sharing their earned wisdom with all of us today.

Virginia Irwin-Scott, National Kidney Care Director at ChenMed

Sharon Pearce, SVP Government Relations at National Kidney Foundation

Shammi Gupta, Chief Medical Officer at Monogram Health

Sri Lekha Tummalapalli, Nephrologist-Researcher at Weill Cornell

Amber Paulus, Kidney Health Researcher at VCU

Alice Wei, Nephrologist and Physician Executive

What you’ll learn

Q&A

Q1. The State of VBKC: At the highest level, how would you describe current approaches to Value-Based Kidney Care in the United States?

TLDR: Our experts describe the evolution and current state of Value-Based Kidney Care (VBKC) in the U.S. as a transformative shift from traditional fee-for-service (FFS) models to outcome-focused, patient-centric care. The move from managing end-stage kidney disease in-center to proactive, upstream care aims to slow disease progression, enhance home dialysis and transplantation, and reduce emergency interventions. Technological innovations and financial incentives are driving a broader industry shift towards integrated care models that emphasize early intervention and improved patient outcomes. These changes are supported by various CMS initiatives and private capital, with an increasing role for tech-enabled models that optimize care delivery and resource allocation.

A1. State of VBKC

Virginia: VBC organizations in the kidney care space initially targeted Medicare patients following the signing of the executive order to transform kidney care. Historically VBC's have either partnered with the payer or the nephrologist, all trying to get to the same end points, controlled cost and improved outcomes. CMS has made it clear the desire to transition patients to Medicare Advantage following the Cures Act in 2021. This is now shifting the alignment and focus into the Medicare Advantage space.

Sharon: For the past 60 years, the kidney care paradigm has focused primarily on managing patients with End Stage Kidney Disease, or kidney failure, mostly in the in-center dialysis center setting. In recent years, however, there's been significant focus on moving kidney care "upstream" so that we can slow the progression of kidney disease, reduce risk for cardiovascular complications, reduce emergency dialysis ("crash") starts, and increase access to home dialysis and transplantation.

Shammi: Value-based care continues to evolve and practicing clinicians are embracing it as the future way practices will be reimbursed. Practices are planning for a time in the near future where a significant component of their revenue will shift from FFS to VBC. Approaches to patient care are shifting from volume based to outcomes based. As better tools are developed to identify the highest risk patients, practices will be smarter in how resources are allocated.

Lekha: Value-based kidney care has never been more exciting. The journey started in 2012 with the ESRD Quality Incentive Program – the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)'s first ever mandatory pay-for-performance (P4P) program. From 2015-2021, we saw reasonable success with ESRD Seamless Care Organizations (ESCOs), which lowered hospitalizations and catheter usage among dialysis patients, but did not result in net savings. All these efforts accelerated with the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) Executive Order which introduced several new initiatives. Within AAKH, the ESRD Treatment Choices Model has potentially increased home dialysis uptake by a small amount, both in Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) and non-Medicare patients. I think the Kidney Care Choices Model through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) – which includes CKD Stage 4/5 and transplant patients in addition to dialysis patients – could be the most promising, but results are still forthcoming. New models through CMMI are also on the horizon, and there are a multitude of value-based contracts administered by Medicare Advantage plans and other payors.1

Amber: I would say the industry is shifting to a kidney health model progressing from a historical disease centric model of care. Due to the silent symptoms of kidney disease our ability to intervene early on in the disease is often limited. The innovation in the field is being influenced by financial incentives made available through innovative models from the federal government in tandem with private equity funding all fueling this shift to value based care.

Large dialysis organizations (LDOs) are diversifying their business models to incorporate population health models into their service lines moving further upstream in kidney care rather than just managing end stage disease. Additionally non-dialysis affiliated businesses are entering the space and growing to meet care management needs as extensions of nephrology practices. These two core approaches are catalyzed by various other innovators including technology businesses that support AI/ML and data platform development, remote patient monitoring products, and risk adjustment services including advanced practice providers to do this specific work through annual wellness visits. Collectively this evolution is pushing the industry towards a more integrated and coordinated system to maintain kidney health, slow progression of disease, and improve outcomes for patients..

Alice: Healthcare in the US has predominantly been a volume based, individualized sick-care model. This model is suited to serve the few that need episodic or acute care. Now however, chronic diseases are the main drivers of death and disability. Longitudinal care management is needed over a longer course, is more prevalent on a much larger scale. Coupled with advanced therapeutic options that are more expensive, healthcare expenditures have become untenable.

A new model of VBC aims to ensure providers of care are accountable to quality, outcomes and cost for populations of people. The overwhelming force in driving VBC today are models that tie payment to the quality of care delivered, outcomes of that care, and the cost. CMS has introduced several iterations of VBC payment models in the past 2 decades. The ESRD prospective payment system introduced in 2008 was the first subspecialty VBC program that prospectively paid for a patient's chronic dialysis treatments and other dialysis related services in one lump sum. This incentivized dialysis providers towards efficiency and cost containment. Subsequent iterations implemented penalties for suboptimal clinical outcomes, encouraged population health management, and monitored utilization metrics. The most recent kidney care VBC model of KCC shifts varying degrees of accountability to the cost of care to the kidney care providers, while incentivizing better clinical outcomes through bonus payments.

Q2. Current barriers: What do you see as the greatest barrier(s) to scaling VB kidney care programs?

TLDR: Our experts highlight several key barriers to scaling Value-Based Kidney Care (VBKC) programs in the U.S., emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis, operational readiness, and robust data integration. Major challenges include integrating primary care more effectively in kidney care management, overcoming workforce limitations and educational gaps in value-based care, and addressing financial ties that impede full adoption of VBKC. Additionally, operational and IT challenges, particularly in adapting to new workflows and data systems, as well as cultural shifts in care practices, pose significant hurdles. Further, the fragmented design of VBC payment models and data silos severely limits real-time data access, complicating the management and scalability of VBKC programs.

A2. Barriers

Virginia: Few organizations are partnering with Primary Care or are the Primary Care Provider (PCP) taking on the kidney care market to be a market leader in controlling cost and improving outcomes. Upstream management requires the PCPs to be the center of the discussion. Early recognition and disease management is crucial to slow the progression. Addressing the polychronic nature of illnesses that often leads to the progression of chronic kidney disease is best suited to be in the hands of the PCP. Many VBC's have moved from just serving the kidney care space to now offering polychronic care management for the complex patients. This has led to confusion for patients as to who is offering what care. Many of the VBC's are looking to "go up stream" these are large population numbers not suitable to chart reviews and "people" management.

Sharon: Underdiagnosis is a huge barrier to CKD care. More than 37 million Americans have CKD but 90 percent are undiagnosed. More than half of people with CKD 3 (mid-stage) and 30-40 percent of patients with CKD 4 and 5 (late stage) are unaware of their kidney disease. Earlier diagnosis and management could prevent kidney damage and cardiovascular complications, delay kidney failure, and improve quality of life.

Shammi: Current barriers include late adopters and the continued hold some large practices have over dialysis providers. The financial link between nephrologists and LDOs are prolific and continue to hinder some of the full adoption of VBC. Other hurdles include the cost for practices associated with managing high risk patients versus all patients.

Lekha: There are major operational, information technology, and cultural barriers to adopting value-based kidney care. Nephrology practices need a great deal of know-how to even sign up for the voluntary programs, like Kidney Care Choices. There needs to be enough organizational readiness to change workflows and protocols in order to succeed in the models. Nephrologists need enough protected time to make care delivery changes and analyze their performance. Implementing data analytics and electronic health record-based interventions is typically expensive, time-consuming, or both. Hiring staff is another major challenge, especially with rising labor costs and nursing shortages. These barriers are why many nephrologists partner with large dialysis organizations or private value-based care (VBC) companies to provide the necessary infrastructure.

Amber: I think the barrier that I feel most concerned about is workforce limitations. It’s not just that there aren’t enough nurses or interdisciplinary care team members to do the work but more critically, there is an education and training gap. There is a curriculum gap in the programs we all train in today to become a member of our chosen discipline. The workforce doesn’t have the knowledge, skills, and tools to move directly into a value based care setting and would need to acquire this skill set on the job which requires time and investment.

Nurses specifically need strong case management skills, an understanding of population health interventions and exposure to what care looks like when we attempt to proactively engage someone in care when a big event isn’t currently or didn’t recently happen. The population we aim to reach also lacks awareness that these kinds of services even exist and why they are important in managing their disease.

In tandem to the nurse knowledge gap exists the similar gap in our physician colleagues who have all trained in a fee-for-service fueled environment where volume has always mattered. Evolving to a value based care mindset requires thoughtful and consistent change management which can be difficult when a providers caseload is only fractionally impacted. For example participating in CKCC through the CMS KCC innovative payment models for CKD 4, 5, ESRD only includes Medicare A & B covered individuals. Physicians aren’t thinking about their patients insurance coverage when delivering care. So the need to evolve would only be financially ‘covered’ in a small population of patients which can be a barrier to buy-in. The idea of ‘needing to practice differently’ for this small subset of patients is operationally challenging.

Alice: Two main barriers deserve prioritization. The first is data silos. Participation with health information exchanges (HIEs), partnerships with physician groups, health plans and hospital systems or dialysis providers rarely provide the seamless flow of data that patients envision. VBC arrangements rely on reconciliation of diagnoses, outcomes and utilization, which in turn rely on claims data, but claims can lag by as much as 6 months. Not having data in real time means providers of VBC mostly operate in the dark. At best, inefficiencies cost patients and providers time and money. Providers of VBC lose the opportunity to pivot their strategies. At worst, patients are vulnerable to serious medical errors or mis-judgement. Being able to assess disease severity, risk of an acute adverse event, or appropriateness of medication are all compromised without comprehensive access to data. These limitations attenuate the scalability of VB kidney programs.

The second high priority barrier in VB kidney programs is the design of the VBC payment models limiting the scope of healthcare provider participation. The focus of these programs and models is on the nephrologist or dialysis provider. Without the alignment of all healthcare providers within the ecosystem of care however, there will be fragmentation of care. Hospitals, primary care physicians, subspecialty care physicians, pharmacies, diagnostic centers, urgent care centers, post-acute care centers all need to align and coordinate efforts at managing the health of a population within a community. This barrier is not limited to VB kidney care, as all VB payment models (from CMS and commercial payors) structure their models around a single healthcare provider type or disease state. A more comprehensive approach is necessary to ensure complete care coordination.

Q3. Solutions: What can be done today to overcome these barriers? Who will need to be involved? What does a great outcome look like?

TLDR: Experts propose multifaceted strategies to address barriers in scaling Value-Based Kidney Care (VBKC), focusing on early detection, education, and integrated care models. Solutions include enhancing primary care partnerships, utilizing AI for CKD management, and advocating for USPSTF screening recommendations. Payment models need reform to incentivize preventive and upstream care. Collaborations with policymakers and ongoing workforce training are vital for adapting to value-based frameworks. Additionally, improving data integration through mandatory participation in health information exchanges and ensuring comprehensive support for EHR adoption are crucial steps forward.

A3. Solutions

Virginia: Until 2030, 10,000 Americans are turning 65 daily and in 2030 20% of the population will be over 65. The Nephrology workforce is not in a place to care for all the Chronic Kidney Disease patients of the future, upwards of 38% of the over 65 population. There will be 1.2 million Americans on dialysis by 2031. We need to scale kidney care today for tomorrows future. Re-imagining how this looks requires partnerships with Primary Care organizations to coordinate the care. The integration of AI with care pathways that include treatment recommendations and monitoring is crucial to the success of PCP managed CKD patients.2

Sharon: A USPSTF Screening recommendation would go a long way to helping the more than 33 million adults with undiagnosed CKD learn of their illness and take the steps necessary to preserve their kidney health. Further, the development and adoption of quality measures that incentivize screening, expand utilization of medical nutrition therapy, increase access to novel therapies, and other actions that delay progression would align payment policy would the clinical practices needed to manage CKD. USPSTF is currently conducting an evidence review to determine whether it will change its recommendations and the National Kidney Foundation is undertaking several initiatives to improve quality measurement in CKD.

Shammi: To overcome these barriers, dialysis income cannot comprise the majority of income for nephrologists. Payment models that reward upstream work and reward use of appropriate pathways (transplant, home dialysis and conservative care) are crucial to practices. Current models to do not pay for services such as conservative pathway management or prevention of dialysis.3

Lekha: Collaborative partnerships with policymakers are a must. I think this has been a true strength of the kidney community. Policymakers at CMS and CMMI should continue to co-design VBC models with nephrology professional organizations and seek their ongoing input. The burdens of data collection and reporting need to be urgently reduced – such as through shorter patient-reported outcomes assessments, electronic clinical quality measures (eCQMs), and focusing on a parsimonious set of measures. Finally, I think there's a huge role for pragmatic trials of care delivery interventions, although these are challenging to execute. Achieving cost savings is tough. While the care team can have some impact to reduce unnecessary ED visits and hospitalizations, a lot of care coordination efforts are ineffective and aren't tailored well to individual patient needs. We're still establishing what best practices look like to improve quality and reduce costs for kidney patients.

Amber: Training and education should be a core function of what it takes to become a value centric industry in kidney care. We are really great about talking about barriers and the inertia to respond in solving those barriers is usually complex. Organizations doing value based kidney care should include this in their personal mix and be sure it’s the right person to train novice individuals to develop in this new model of care. I could see a company forming to solve this very specific problem offering what would traditionally available in a college curriculum in an online intensive or weekend onsite that any value based care org could leverage to train up their workforce and support ongoing education through CEUs, certifications, micro certifications, etc.

On the provider side what I just described would support their development as well. But also in day-to-day operations a field team that really partners with providers to support practice transformation is important. At the end of the day I do believe this value-based model of care will become the way we do medicine and fee for service will sunset as a reimbursement strategy. So even if a small portion of a providers patient population is impacted through federal programs today— an opportunity currently exists to be an early adopter. The financial incentives that exist today will not always be available.

Alice:

1. TEFCA was directionally a good step. However, participation in HIE's and QHIN's is still voluntary and there are ~20% of physician practices that do not use EHR's. More could be done to support these practices in adopting EHR's and participating in HIE's. Participation in QHIN similarly could be supported and mandated.4

2. The solution to the second barrier requires strategic discussions with experts from varying fields in healthcare and VB program architects.

Q4. Policy: How do you think about current federal programs, incentives, and policy levers in the context of other parts of your business like risk, contracting, capital needs, or people?

TLDR: Experts express mixed feelings about the effectiveness of current federal programs and policy levers in advancing Value-Based Kidney Care. While these initiatives have catalyzed significant shifts towards patient-centered and performance-based approaches, they highlight the need for broader educational reforms and more effective risk models. Challenges remain in significantly moving the needle for home dialysis adoption, despite incentives. There is a consensus on the need for more comprehensive training for nephrologists, improved participation opportunities for small practices, and a reduction in the administrative burdens of quality reporting. Additionally, a holistic policy approach that encompasses lifestyle education and addresses broader social determinants of health is seen as essential to truly elevate patient outcomes in kidney care.

A4. Policy

Virginia: What has been most disappointing to me as I now have direct line of sight over a large population of advanced CKD patients across the country, is that even with all the incentives and programs we are not moving the needle for home dialysis by large percentage points. Nephrologists need to be the ones who take ownership to make this change. As Tim Fitzpatrick's recent post pointed out training programs for nephrologists need to take ownership for providing adequate training for PD and HHD knowledge. RPA and other organizations have taken a position of support for this as well.

Our first thought should always be home and not offering up excuses as to why the patient is not a candidate. All patients should be given education and choice. The patient-nephrologist relationship is often a decade, sometimes longer. The patient and the nephrologist should make the treatment option decision, together.

Shammi: Risk models work. Doctors tend to be a confident bunch that is also driven. If given meaningful opportunities that allow the doctor to develop patient centered approaches as opposed to volume based approaches would be welcomed. Also- allowing even small practices to be part of VBC arrangement at the practice level would encourage more participation.

Lekha: There has been a proliferation of quality measures which unfortunately, have major limitations. Often, they lag in being up-to-date with the latest clinical guidelines, and are burdensome to report. Although CMS is emphasizing outcome over process measures, risk adjustment can be problematic, so I still think process measures play an important role. I also think having a comprehensive policy approach is crucial for VBC programs to succeed. Legislative and regulatory efforts to improve the workforce, reimbursement, and other issues can "rise all boats" in both FFS and VBC.

Amber: Most folks in the industry likely don’t spend absorbent amounts of time thinking about federal levers. I could probably talk about this topic for hours. The field of nephrology has been center stage for the federal government as a pilot in pay for performance innovations since the ESRD quality incentive program launched in the federal register 2011 and then implemented in 2012. While this was limited to the dialysis facilities it gave the field the first taste of reviewing metrics and organizing care to achieve better performance. Initiatives like “fistula first” launched to impact our high central venous catheter use which inherently puts patients at higher risk for poor outcomes. We started looking more closely at adequacy in our patients (KtV), transplant waitlisting and organ recipient and many other measures.

While most would say the reporting of this information is administratively burdensome - as a whole it’s driven innovation through how this data is leveraged, made public, and then used to create solutions to improve how care is delivered. The various iterations of the federally sponsored innovative payment models — ESRD CEC (ESCO), ETC, and KCC — have created progressive environments for reorganization of care delivery. KCC provided an option to move further “upstream” from ESRD focused models. This is providing an opportunity for nephrologists and care management orgs to implement interventions to slow disease progression and maintain kidney health. Overall I do think the QIP has been a positive influence on the industry. And while we are early in the KCC implementation, great results are being achieved in reducing acute care utilization and I look forward to when the data goes public for a better understanding of the progress that has been made..

Alice: Policy and federal programs continue to shift risk of care to providers of care. But the tenants of wellness and good health are largely being ignored, and younger generations are largely ignorant of those tenants. There is a tremendous opportunity and obligation for our public school systems to help children understand and develop habits that promote health and wellness: balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, quality sleep, meaningful relationships, avoidance of tobacco, excessive alcohol or recreational drug use. Federal funding should be tied to meeting a standard curriculum of health and wellness. Regardless of the program of care delivery or payment model, medicine cannot undo decades of poor lifestyle or environment. Medications, vitamins and supplements cannot make up for food swamps. VB kidney care cannot mitigate the impact of a violent neighborhood.

Access to healthcare and the quality of that care is estimated to account for only 20% of health outcomes, including mortality and quality of life. From housing quality to recreational spaces in nature, education and economic opportunities, policy and federal programs have enormous impact on the major determinants of health.

Q5. Future directions: Looking ahead, where do you see the most important proving grounds for these care models and programs?

TLDR: Experts envision crucial proving grounds for Value-Based Kidney Care models focusing on early identification and management of CKD, integration of AI for personalized care, and routine CKD testing within standard healthcare practices. Emphasizing technology’s role in enhancing diagnostic and treatment precision, they advocate for annual CKD screenings for at-risk populations and widespread use of medical nutrition therapy. They also foresee the adoption of advanced risk adjustment techniques and a stronger emphasis on social and emotional aspects of patient care. The overarching goal is to shift focus from end-stage management to preventative care, ensuring long-term continuity, coordination, and commitment to kidney health across all care settings.

A5. The Future

Virginia: When organizations like my own predict the future of 1 million covered lives, that is 380,000 CKD patients, and nearly 20,000 ESRD patients under the care of Primary Care. The future of kidney care is the identification of the upstream patients who are likely to progress to ESRD and intervening early to slow the progression. Only 2 out of 100 patients will progress to ESRD. They are the CKD survivors. Early identification, education and proper medication management will lead to success. We can not offer all the "expensive drugs to everyone" we need to properly identify and strategically mange kidney care. What excites me the most is the role that AI will play in guiding us with recognition and care management. Large organizations have the structured data needed and through large language machine learning and predictive AI we will continue to improve identification and treatment guidelines allowing patient care to be tailored and targeted. PCPs and specialists in the future will be supported by large language models (e.g. ChatGPT, LLaMA) providing them instant chatbot access for medical management. Technology will be the support and no longer the hindrance.

Sharon: CKD testing, diagnosis and management would be a routine part of health care, similar to blood pressure control. CKD screening would be annual for at risk populations (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, family history, and other risk factors). General population screenings would also be recommended, perhaps, less frequently, but sufficient to ensure timely diagnosis. Finally, therapies such as medical nutrition therapy (MNT), prescribing of cardio-renal protective drugs, and other therapies would be available, accessible, and affordable for patients.

Shammi: If we get this right, patients will be given the "right" options for them in a way that not only addressed their physical needs but social and emotional needs also. Dialysis would be used appropriately and not be used to prolong death but to prolong life (waiting for transplant). Systems would attack social needs and behavioral health needs holistically and realize that they are sometimes more important than the standard medical risk factors. Physicians would be paid for quality and manage fewer patients (more complex) and drive outcomes and be paid accordingly.

Lekha: Three things come to mind – continuity, coordination, and commitment. Kidney disease doesn't develop overnight. Diabetic kidney disease, for example, can take 15 to 20 years to develop, during which time a patient will have multiple changes in their primary care physician (PCP) and insurance. Patients need a care team with a long view to ensure they receive optimal guideline-directed medical therapies over years and decades. This optimal care requires coordination among all specialists, so that a patient's PCP, nephrologist, endocrinologist, and cardiologist are on the same page, and the patient can receive an ACEi/ARB, SGLT2i, MRA, and GLP-1 RA for as long as possible. There's definitely a role for e-consults, synchronous multi-specialty clinics, and other forms of co-management here. Lastly, both the care team and patients need to be committed towards improving kidney health. The medical community and public need to recognize the importance of early detection of kidney disease (through urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio screening) and treatment, both for preventing kidney failure and reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. I think there's ample room to incorporate kidney health within broad-based programs, such as the CMS Universal Foundation, APM Performance Pathway, and ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Model.56

Amber: I dream of a world where dialysis is considered an extreme intervention where more of our healthcare resources and costs are invested in health maintenance. I look forward to seeing a greater emphasis on health equity and assessing of patients social determinants of health to design effective care plans for individual patients. There’s some really radical things I hope for that I’m not sure will happen.

I really believe in the capability of people called to enter the medical field. In a world where you can be and do anything I think we should keep those relationships as the central connection to patients. Nephrology is great at consolidation as evidenced by having two major dialysis providers. My hope that the growing trend of care management companies still keeps the nephrologist relationship as the central component of care.

I’d love to see risk adjustment techniques go open source or published by the federal government that would level set the industry and allow clinicians to use that information at the point of care in their own internal systems without having to partner with an outside entity to get the kind of capability. I acknowledge that sounds crazy but nephrologists are doctorally-trained individuals who go through extensive training. If equipped with information that allows them to make better clinical decisions at the point of care— I think success in value based care is completely possible. Some things don’t need to be proprietary.

Alice: In recent years there has been increased attention on disparities of health outcomes. This was brought to light when population health outcomes were segmented into various sub-populations. The focus is now on ensuring more equitable care. Asking the question, how can we deliver what the patient needs to reach their optimal level of health and wellness? This approach will need to be preceded by soliciting patient directed goals.

Q6. Story time! I’d love to hear about any experiences or situations where nutrition played a critical role in improving a patient’s life.

Virginia: Coming from Southern New Jersey as a practicing nephrologist for 2 decades, I did not have a full grasp of the discrepancies in care throughout various parts of the country. I had practiced "optimal starts" my entire career. Only doing outpatient CKD management for > 15 years, I believed that all nephrologists had optimal start rates of > 90% (patients sitting in an outpatient clinic with matured access, listed/referred for transplant, and 30% home penetration).

I quickly found out that this was not the case.

The patients I am now responsible for get their Medicare Advantage Insurance and show up to a clinic for their first visit— the first visit in decades. Often the first labs reveal a Hgb A1C of 14, GFR 14 and Hgb of 8. There has been no opportunity for a decade of CKD education or intervention. Working with the PCPs over this last 1.5 years, supporting these patients, gaining their trust and helping them get into the hands of nephrologists has been so rewarding. What fuels me everyday is having a dedicated team of RNs with experience from the kidney care world who educate the patients and coordinate their care.

We cheer every optimal start. We cheer every PD start. We take none of what we do for granted.

We have seen an 81% growth in PD in the last 2 years. We have driven down hospitalizations and rehospitalizations below industry standards with a DaVita partnership. It really comes down to communication and coordination of care. I now see the other side of the noncompliant dialysis patient, those who do not have clinics to dialyze at related to Mental Health issues or Behavioral issues and the struggles to secure them adequate dialysis is real. Often patients have made bad decisions early in their dialysis journey. Those decisions may impact their access to dialysis for a long period of time. Even when they are willing to recognize, take ownership and change getting them into a facility is often difficult. We have to develop a better access plan for these patients.

Shammi: As I care for patients, I am able impart on my team the dynamic nature of dialysis patients. Their situations change as they progress medically. Sometimes a patient is a transplant candidate but the longer they wait, they lose their window and now need to shift to palliative. We have patients that start in center and learn they can do home. I have been able to educate my team about this and they are better equipped to help dialysis patients understand their options.

Lekha: Our work with the American Society of Nephrology Quality Committee has been particularly meaningful. We conducted an environmental scan of 60 quality measures within nephrology. Unsurprisingly, we found that measures heavily focused on dialysis care, and there was a paucity of measures for CKD. This led us to work with the Renal Physicians Association who submitted an ACEi/ARB measure to CMS for use in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). We also worked with CMS to design a MIPS Value Pathway called "Optimal Care for Kidney Health" which includes measures most relevant to nephrology care.

Amber: The conversations I have in my every day work including virtually on LinkedIn keep my brain constantly innovating new approaches to support the evolution of value based care. Perhaps one of the coolest things I’ve experienced in the last 6 months was so unexpected it’s worth sharing. Prior to my transition out of academia I started sharing on LinkedIn really to develop a creative outlet that still forced me to write and try to synthesize my ideas (a key skill in academic success). But as I transitioned into industry based work my writing started to reflect what I was learning and really how I was conceptualizing the work. I wrote a post about this idea of managing risk in a population and and an active writer on LinkedIn, Michael O’Brien, wrote a comment about the way he has thought about de-risking a population through prior work he had led.

It was so simple— but it was the use of the word “de-risk” that had my wheels turning.

I’d never heard of the term and it’s probably not even a proper term but it led to the conceptualizing of CATCH — Cohorting Analysis to Control Healthcare expenditure. CATCH organizes what I'm referring to as the “vital signs” of value based care - high risk, high cost, and high utilizer and now provides a framework in which I teach nurses patient prioritization and share with providers cohorts for interventions.7

A second story also stems from an unexpected conversation. The reason why I transitioned into industry from academia was because an influential nurse leader. Throughout my career as a nephrology nurse I have benefited from investment from mentors who have taken an interest in me and my development as a nurse. When I came to my current position Angie Kurosaka made a significant impact on my professional development and really helped me find my voice in the field of value based care. Together we have tried to articulate how nurses can lead in value based kidney care and why their roles are so critical in building the workforce needed to achieve the ultimate goals of Advancing American Kidney Health. We developed a framework termed HEALTH that we’ll share for the first time in an upcoming publication in the Nephrology Nursing Journal and we’re both presenting on value based care at the National Symposium American Nephrology Nurses Association (ANNA) in April. Continuing to support the conversation and enhance understanding of what value based kidney care is, is really important to the success of this new model of care.

Alice: I began my career in medicine before the concepts of Social Determinants of Health or Health Equity were widely known. A particular patient helped me appreciate these concepts. For this sedentary gentleman with high blood pressure and poor sleep, I wrote on a prescription pad "Walk through nature or a park x 15 minutes 3x per week". I thought it help his mood and give him some exercise. When he returned three months later and admitted he hadn't followed the "prescription", I was curious why. He told me drug deals were common in the park near his home, and it wasn't a safe place to be. Could he take the stairs in his building for exercise? No, the stairwells were another unsafe place.

This was the first time I realized there were much larger issues that were impacting my patient's health than genetics and lifestyle choices.

Everyone in healthcare needs to understand these concepts because there are complex problems that need solving and we need everyone's brainpower and creativity to help! I created a Health Equity initiative that focused first on a self directed educational journey through a curated curriculum. It was inspiring to see teams independently create goals around this initiative.

Q7. What’s something people should know about this space or your company that they may not know already?

As we navigate the complexities of growing value-based care, I like to ask our experts to share any questions or resources that might spark further discussion. It’s an open mic format, so please feel free to leave a comment if any of these resonate with you. Consider this your invitation to engage in the discussion!

A7. Did you know?

Virginia: ChenMed is a full-downside risk Medicare Advantage Organization caring for patients in the most at-risk areas of the country. We offer high quality care in a supportive model. High touch PCP visits with care coordination and robust resources: ChenK Kidney Care management, Care coordination with Acute Case Management, in center pharmacy, lab and basic x-ray services. We have in-house care coordination with Cardiology; Podiatry and Wound Care are coordinated through our National Director of Vascular Surgery. We offer acupuncture as an alternative for pain management. Social Work support helps to identify and assist in SDOH, we offer transportation and coordinate specialty care. The clinics become a haven of support serving a community.

Shammi: At Monogram we are pushing VBC to the next level. Not only do we work with existing community based doctors we also provide direct care to patients. Our unique NP led model has our NPs focus on polychronic conditions while in the home supported by a POD based model. In addition to caring for those with CKD, we also focus on their common comorbids (DM, CHF, COPD, BH, and SDOH). Our model focus on pharmacy and our own pharmacists work with our clinical teams to drive best outcomes. Our NP led model is supported by our local medical directors who oversee care and have access to our Monogram Health centrally based specialists to offer real time support for urgent care or chronic care. These specialists include cardiology, pulmonology, endocrinology, nephrology, and behavioral health. Bringing health care to those at highest risk is an imperative for us. Our approach to VBC is changing the way healthcare is delivered to those most in need. Our focus on doing what is best "now" leads to patient centered outcomes at the point of care.

Amber: Value-based kidney care is the way we should have always approached healthcare in this country. It’s the kind of care you would want for your loved ones. However, working in value based care brings you up close and personal with the brokenness in our current system. Because of this I believe there’s room for everyone who have a desire to improve healthcare for our country. I don’t subscribe to the competitive conversations that are often common in nephrology and would challenge any one reading this to stay focused on your mission and vision as an organization. Refrain from the comparison game of your perception of how others are performing and let your results speak for themselves.

Resources & Data

I asked the experts to help us curate their favorite resources and recommendations where you can learn more about these topics. Here are their must-read deep dives:

Reports

Risk On: Value-Based Kidney Care Is Here. I wrote this Signal following the January CMS update on on its KCC Model participants for 2024, which includes 123 participants, over 9,200 providers, and more than 280,000 beneficiaries. The model itself can be a bit daunting, but it doesn’t have to be. I put together this graphic to help you understand the basics of the model, its overall aims, and what the various risk options and benefits entail.

Table: Value-Based Kidney Care. This is one of our most popular Signals to date. In this post you’ll meet 11 companies in the arena who manage roughly twice as many lives and upwards of $15 billion in annual spend. This reference guide will help you get up to speed quickly on their respective journeys to improve the cost and quality of kidney care delivery in the United States.

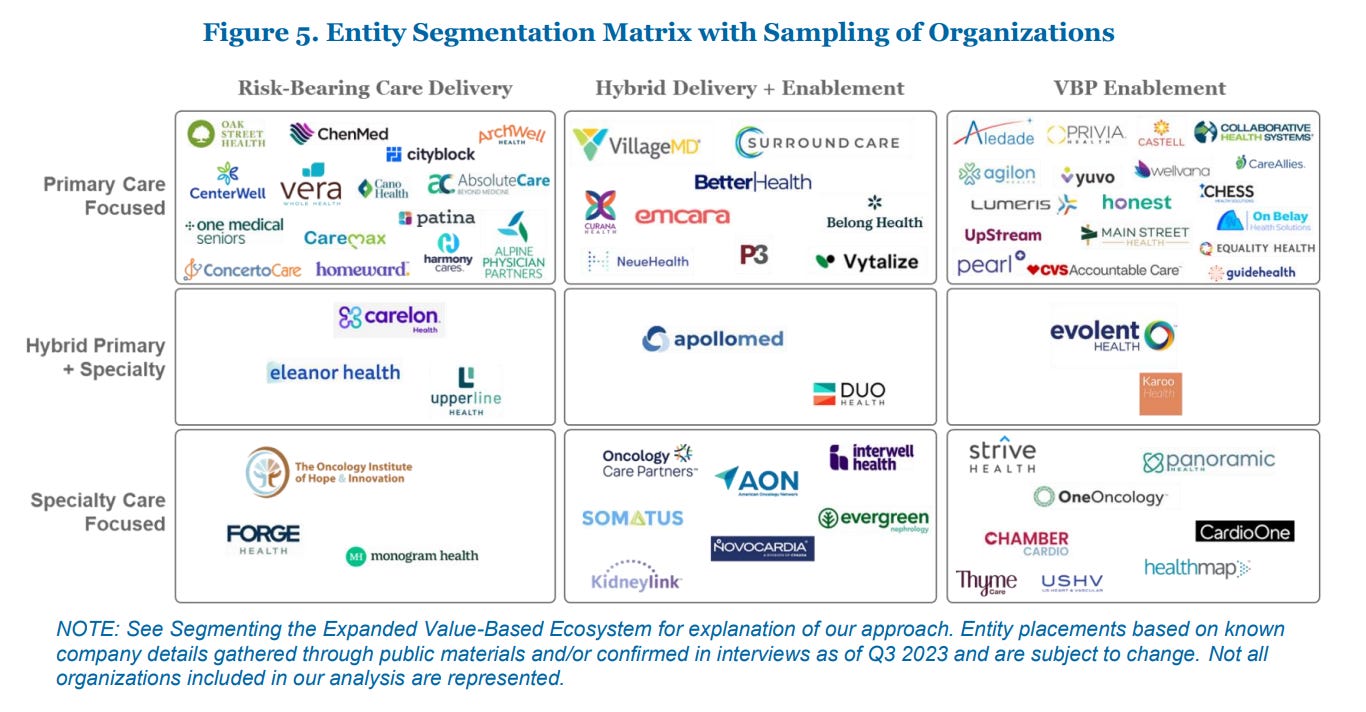

Analyzing the Expanded Landscape of Value-Based Entities. This recent in-depth report from HMA and Leavitt Partners analyzes the landscape of emerging value-based entities and the implications for accelerating the adoption of accountable care. It’s a must read if you’re looking for a deep dive into VB market segmentation and differentiation in care vs. enablement vs. hybrid models.

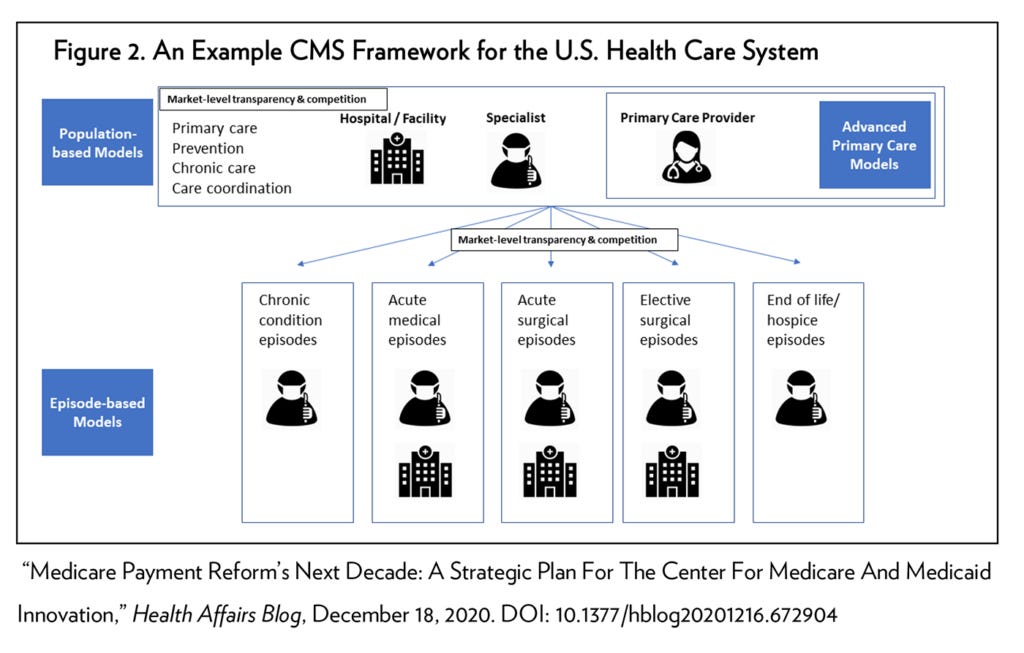

The Future of Value-Based Payment: A Road Map to 2030. This white paper from Penn’s LDI outlines a new direction for the federal government—primarily through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)—to chart over the next decade aimed at completing the transition to a health care system that pays for value and reduced health disparities, rather than high volumes of services.

Silicon Valley Bank’s Annual Investments and Exits Report for 2023 gives us an overview of fundraising, investment and sector outlooks across healthtech, devices, and diagnostics. The 5 largest healthtech rounds of 2023 account for over $2 billion raised — and most of that is value-based care with two mega rounds ($100M+) in kidney care (Monogram and Strive).

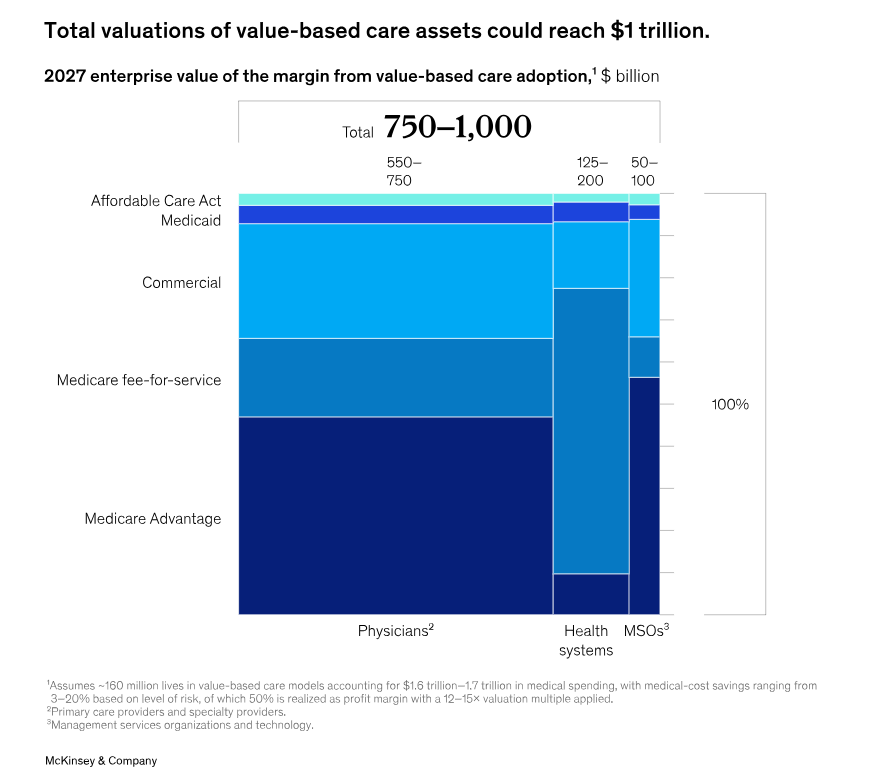

Investing in the new era of value-based care. This 2022 McKinsey & Co. report takes a more expansive definition of the value-based care landscape and includes all care models that align provider incentives to quality or care cost-reduction. The authors believe that by building on a decade of increasing value-based payment adoption, continued traction in the value-based care market could lead to a valuation of $1 trillion in enterprise value for payers, providers, and investors.

Research & Commentary

Value-Based Care and Kidney Disease: Emergence and Future Opportunities (Tummalapalli SL, Mendu ML. ACKD, 2022)

Disrupting Kidney Care [Round 6] with Dr. Qasim Butt — a webinar with Drs. Virginia Irwin Scott, Shammi Gupta, and George Hart.

US kidney care is broken. But we have the means to fix it — By Alex Azar, published in The Hill on March 4, 2024.

Value-Based Care Catalyzes Transformation of Kidney Disease Care — Healthcare Innovation, 2022

Thanks for tuning in for this Expert Q&A. Please share this strong dose of optimism with your corner of the Kidneyverse — and if you find this information valuable, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber today!

Value-Based Care and Kidney Disease: Emergence and Future Opportunities (Tummalapalli SL, Mendu ML. ACKD, 2023)

Baby Boomers Approach 65 – Glumly (Pew Research)

Should Your Kidney Doctor Have a Financial Stake in Dialysis? (Sci Am, 2020)

Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) (HealthIT.gov)

ACE Inhibitor Benefit to Kidney and Cardiovascular Outcomes for Patients with Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 3–5: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Clinical Trials (Zhang Y, et al. Drugs, 2020)

ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) and Kidney Care Choices Models — PY2024 Risk Adjustment (CMS)

Read Dr. Paulus’ CATCH posts on LinkedIn

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4d588ac1-7fac-4bd4-829d-fc7b4e8f1326_1512x288.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F55686857-6b99-45a6-ac0f-09c9f023f2a0_500x500.png)